I recently had the opportunity to help lead a Penn course on sustainability and the food-water-energy nexus, with an emphasis on food waste. The bulk of the course consisted of a week-long trip to Italy.

Why Italy? First, why ever not? Second, course instructor Steve Finn wanted to explore food waste through the lens of Italy’s passion for food, especially in the wake of EXPO Milano 2015. And explore we did!

We held sessions with UN FAO staff in Rome, interfaced with professors and students at the University of Bologna (like the amazing Silvia Gaiani), and visited the Food Innovation Program in Reggio Emilia. These exchanges were educational and enlightening, especially in promoting cross-cultural interaction. Each time, it felt like we were at the UN, and in one case we were!

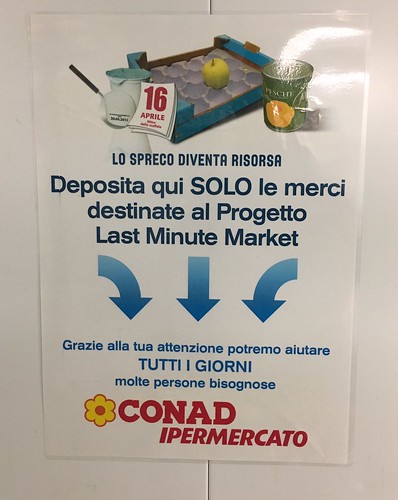

The class engaged in plenty of experiential learning, too, visiting a Parmigiano Reggiano maker, a balsamic vinegar producer and a supermarket hell bent on preventing food waste via the Last Minute Market program.

Another exceptional experience in Italy is simply eating. Anywhere. We observed a pervasive passion for food in Italy. I won’t soon forget the care and theatrics that a Bologna waiter exhibited when tossing and serving a Tagliatelle Bolognese.

You’d assume that that passion would translate into less wasted food. And you could say the same about lingering memories of Italy’s post-World War II poverty and hunger. Yet, Italy’s food waste score ranks below that of the US and many other European countries in a recent sustainability index.

How can waste, or “lo spreco,†be so prevalent? The coexistence of Italian food waste and food infatuation illustrates the global spread of negative culinary trends. Bigger supermarkets and large package sizes enable and entice over-purchasing. Food costs are artificially low. Hospitality often leads to over-serving. There’s little appetite for leftovers or doggy bags. And maybe, just maybe, Italian food passion leads to perfectionism and picky purchasing.

Fortunately, Italy is doing its best to combat wasted food. In 2013, the government created a national Food Waste Prevention Plan to tackle waste. In 2016, the Italian Senate passed a more specific bill that offers incentives to businesses who donate food to charities and funds programs to tackle food waste in schools and hospitals. Meanwhile, public opinion is firmly against waste, as roughly half of Italians believe too much food is wasted.

Leading activists have run the Zero Waste (Spreco Zero) campaign since 2010. Italian retailer Coop collaborated with Slow Food to create the 100 Faces Against Waste selfie campaign. And Last Minute Market, operating since 1998, has streamlined the process for supermarkets seeking to minimize excess food and donate the rest to charities.

We visited an “ipermercato” (a hypermarket–certainly a more fun term than ‘superstore’), to see LMM in action. The market we visited was a Conad, which was fitting because Last Minute Market’s creators launched the idea in that chain. The store had multiple 50%-off sections to sell older goods. The items that didn’t sell after a day there would then be donated. Additionally, we observed imperfect produce and items with damaged packaging set aside for donation. To facilitate those tactics, the store has one employee, Mary, who dedicates half of her work time to minimizing waste and tracking food donations.

We visited an “ipermercato” (a hypermarket–certainly a more fun term than ‘superstore’), to see LMM in action. The market we visited was a Conad, which was fitting because Last Minute Market’s creators launched the idea in that chain. The store had multiple 50%-off sections to sell older goods. The items that didn’t sell after a day there would then be donated. Additionally, we observed imperfect produce and items with damaged packaging set aside for donation. To facilitate those tactics, the store has one employee, Mary, who dedicates half of her work time to minimizing waste and tracking food donations.

As we left the market, I reflected on the dual nature of our visit. It was both energizing and sobering. It was exciting to see the depth and breadth of the Italian food waste movement. Yet, it was both disappointing and puzzling to see how Italy–the home of Slow Food and dozens of regional cuisines older than the U.S.–had come to waste so much food. Because if the weed of waste can prosper in the garden of food-loving Italy, it can do so anywhere.